FDA update on whole genome sequencing

Kantha Channaiah, director, Microbiology, AIB International, works in the lab to validate the lethality of the cookie baking process. Courtesy of AIB International.

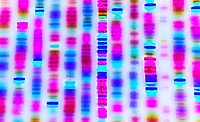

In the food safety world, the FDA is using whole genome sequencing to identify foodborne pathogens during outbreaks. In the long term, the hope is to reduce foodborne illnesses and deaths, both in the U.S. and in other countries.

Addressing pathogen prevention

“Pathogen source-tracking, or precise identification of sources of contamination in a farm-to-fork model during a multi-state foodborne illness outbreak, is often challenged by the presence of multiple ingredients sourced from any number of geographic locations around the world,” says Kantha Channaiah, director, microbiology, regulatory, AIB International, Manhattan, KS.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis results in the highest level of bacterial strain identification during a foodborne illness outbreak investigation, thus helping in precise identification of the source of foodborne pathogen contamination, he says.

“Furthermore, WGS helps in linking foodborne illness outbreak cases associated with various food products spread in different geographical locations to an outbreak source in a farm-to-fork model,” Channaiah notes. “Most importantly, WGS facilitates epidemiological investigation by comparing the DNA fingerprints of pathogenic bacteria isolated from sick people to the adulterated food products responsible for the foodborne illness outbreak.”

Whole genome sequencing is accurate, rapid and can also be used for predicting resistance of a particular bacterial pathogenic strain to biocides, metals, or antimicrobials, he adds.

“When properly implemented, the WGS powered surveillance system can act as an early warning tool in the identification and removal of contaminated food products in a supply chain before the onset of outbreaks.”

Due to its accuracy, low cost and timely data, WGS is increasingly used by the FDA, USDA-FSIS and CDC in foodborne illness outbreak investigations, Channaiah says.

“It is also used to monitor contaminated foods across the supply chain, thereby facilitating more targeted risk assessment and effective public health management.”

Recent developments

Whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic platforms have emerged as a game changer and are evolving quickly, particularly in food safety management systems, says Channaiah.

“However, a lack of validated standards such as sequencing technologies and their bioinformatics platforms among laboratories are posing a significant challenge,” he notes.

There has been a considerable evolution of WGS data analysis methodologies in the last several years, Channaiah says.

“New generation sequencing technologies such as novel Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencer has emerged as the new standard in WGS due to its rapid, cost-effective, portable and real-time analysis of long DNA or RNA fragments. Also vital in analyzing complex genomic data and to develop phylogenetic trees is the selection of several bioinformatics software tools into a pipeline or workflow. FDA and CDC both have developed a custom workflow to analyze SNP-based (single nucleotide polymorphism) subtyping and genome analysis.”

Currently, there are two popular methods in WGS-based subtyping foodborne pathogens: whole-genome SNP typing (WGST) and whole-genome MLSP typing (WGMLST), Channaiah notes.

FDA’s GenomeTrakr program

Launched in 2012, the FDA’s GenomeTrakr program is “creating a sustainable network of public health laboratories using whole genome sequencing (WGS) to investigate foodborne illness outbreaks and attribute illnesses to specific food products, processing or farming practices, or geographic regions.”

“The GenomeTrakr genomic epidemiology network comprises over 50 national and international laboratories contributing genomic data for foodborne pathogens—28 of these in these in the US were just awarded a grant through the Laboratory Flexible Funding Model that will cover genome sequencing costs for surveillance of foodborne pathogens,” says Ruth Timme, research microbiologist, FDA, College Park, MD.

“An additional 5 laboratories were also funded to build new WGS capacity at their facility. This expands the FDA’s GenomeTrakr WGS Network to include 15 new State laboratories for a total of 33 US members, effectively doubling our national network,” she says.

The GenomeTrakr network has directly contributed 141,475 pathogen genomes to date, for the major foodborne pathogen species, including species of Salmonella, E. coli/Shigella, Listeria, Campylobacter, Vibrio, and Cronobacter, Timme says.

Other major achievements this year include full implementation of the open source “GalaxyTrakr,” a universally available and cost-free genomic epidemiology analysis dashboard tool for all network members, she says.

“The tool is used by our state and international network partners, enabling them to custom analyses on their own public and/or non-public datasets,” Timme notes.

This year, additional international training and data sharing workshops were funded for the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Food Safety Cooperation Forum (FSCF) including Partnership Training Institute Network (PTIN) endorsement for a project entitled, “Whole Genome Sequencing: Laboratory Capacity Building for Environmental Food Safety Testing,” to be conducted throughout the APEC region over the next three years, says Timme.

“One of our most significant international programs in FY20 is the renewal and expansion of the GenomeTrakr Latin American Water Project, where academic partners from five separate countries including Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Argentina are engaged in collecting environmental Salmonella from surface waters in these areas. They then sequence and uploading 1,000 isolates to the GenomeTrakr database through the collaboration between FDA-CFSAN and The University of Maryland’s Joint Institute for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (JIFSAN),” she explains.

Preventing pathogens with GenomeTrakr

“These data have helped support more than 230 compliance actions and food contamination events this year, totaling more than 690 foodborne contamination events since the start of the program,” says Timme.

The economic benefit of these networks could potentially save billions of dollars a year reducing the burden of foodborne illness by removing contaminants early from the fresh produce supply, she notes.

“Preliminary economic analysis clearly documents the impact of WGS to public health and food safety. This FY20 year’s strengthening of international and domestic partnerships around the GenomeTrakr network are already opening shared data pipelines and enabling foodborne surveillance and more rapid traceback of foodborne illness on an intercontinental scale—i.e., the recent recall of internationally traded enoki mushrooms,” Timme adds.

“Moreover, the continued expansion and metadata improvements of the GenomeTrakr database has further served to refine its attribution capabilities with predicted isolates from food processing environments now correlating with accurate GenomeTrakr linkages more than 90 percent of the time for domestic facilities.”

GenomeTrakr recent developments

“In the past year, we rolled out ‘direct data submission,’ removing FDA’s GenomeTrakr team as the data broker,” says Timme. “This best practice was published as a preprint (now accepted and in press). As of summer 2020, all GenomeTrakr laboratories are now performing their own quality checks and submitting their data directly to NCBI. This might seem like a minor change, but it’s hugely significant to our program, enabling us to expand as a network without the data management overhead.”

“Any laboratory with genomic capability can follow our best practices and contribute to genomic foodborne pathogen surveillance without official or direct collaboration with GenomeTrakr,” she says. “These independent tools and protocols can be used for ANY genomic epidemiology program, including hospital acquired infections, or more timely, SARS-CoV-2.”

There is also a new public hosting site for GenomeTrakr-related protocols, including genomic data collection and submission to NCBI (public database, hosting GenomeTrakr data), Timme says.

“[We also added] expanded genetic screening for GenomeTrakr isolates: NCBI Pathogen Detection surveillance platform is now screening virulence and stress response genes, and nearly a half-million pathogen genomes have been screened to date. ‘Stress genes’ for these pathogens include biocides, metals, acids, and droughts,” she adds.

GenomeTrakr member labs initially focused their whole genome sequencing efforts primarily on Salmonella and Listeria pathogen isolates, says the FDA website. However, “performing whole genome sequencing on other foodborne pathogens will further leverage the public health benefits that can be derived from the open sharing of the genomic information.”

To this end, FDA and its partners are also sequencing E. coli, Campylobacter, Vibrio, Cronobacter, etc. isolates, as well as parasites and viruses, they say.

“Many public health laboratories have pathogen isolates from past outbreaks stored in their freezers. These isolates hold a treasure trove of genomic information waiting to be unlocked by whole genome sequencing. FDA encourages those labs to sequence those isolates and upload the genomic information to the GenomeTrakr database at NCBI,” the FDA says.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!