Processors must ensure their PCQIs are qualified, trained and experienced

In some plants, PCQIs responsible for food safety plans, which outline bacterial testing, are new to the industry or trained through internet courses.

Photo courtesy of Getty Images

Food processors have a mandate to ensure that they have someone with a new title on board: the preventive controls qualified individual, or PCQI.

Under the definitions finalized in 21 CFR Part 117.3 of the Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food, a preventive controls qualified individual means:

“… a qualified individual who has successfully completed training in the development and application of risk-based preventive controls at least equivalent to that received under a standardized curriculum recognized as adequate by FDA or is otherwise qualified through job experience to develop and apply a food safety system.”

A perusal of the regulation defines the role and duties of the PCQI. These duties are summarized in 21 CFR Part 117.180. The citations specifically define what makes up each of these duties of the PCQI:

- Preparation of the food safety plan (§ 117.126(a)(2))

- Validation of the preventive controls (§ 117.160(b)(1))

- Written justification for validation to be performed in a timeframe that exceeds the first 90 calendar days of production of the applicable food

- Determination that validation is not required (§ 117.160(c)(5))

- Review of records (§ 117.165(a)(4))

- Written justification for review of records of monitoring and corrective actions within a timeframe that exceeds 7 working days

- Reanalysis of the food safety plan (§ 117.170(d))

- Determination that reanalysis can be completed, and additional preventive controls validated, as appropriate to the nature of the preventive control and its role in the facility’s food safety system, in a timeframe that exceeds the first 90 calendar days of production of the applicable food

The regulation also states that these duties may be performed by one or more PCQIs, that a company’s PCQI need not be an employee and that some of these tasks, such as record review, may be done by a trained individual under the supervision of a PCQI. So, although the PCQI or PCQIs have full plates, they do not need to do everything themselves—provided they have taken the time and made the effort to train someone to do work under their supervision.

The two most challenging tasks for PCQIs are the development of the food safety plan and validation of the process preventive controls. Going hand in hand with this last point is making a decision as to whether a preventive control requires validation.

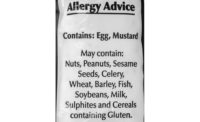

Remember, the regulation specifically states that allergen, sanitation, supplier and recall preventive controls need not be validated. But there is nothing to prevent a company from going beyond regulation.

For example, many processors that are manufacturing foods that contain allergens have taken the time and made the effort to validate their allergen cleaning programs. This strengthens their overall program and further protects the consumer.

So, let’s take a step back and look at what the FDA is asking of the PCQI and how we might define the position. Given the two main challenges highlighted in the previous paragraph, the PCQI must be a food safety expert and a process authority, or someone with similar expertise.

Without significant, broad-based knowledge in these two areas, the PCQI would be under enormous pressure to accomplish the tasks defined in the regulation. The greatest gap in knowledge would be the process authority. There are many persons in the industry who may deem themselves to be process authorities, but not all of them possess the necessary background, knowledge and expertise to develop and validate food safety processes.

Let’s consider an example from the Almond Board of California, which has mandated that California almonds be processed to ensure safety in response to salmonella outbreaks attributed to raw almonds. Processes must be established and validated by process authorities recognized by the Almond Board of California.

The following criteria were used as a basis for what was expected from a process authority:

- Knowledge about product characteristics and equipment used for the treatment process, which would include access to the necessary equipment and microorganisms needed to do the work

- Experience in conducting appropriate studies to determine the ability of equipment to deliver the appropriate treatment, which would include any necessary microbial challenge studies

- Ability to evaluate whether data gathered is sufficient to identify the critical factors needed to ensure the safety of the final product

- Expertise to evaluate the ability of the processor to adhere to the requirements of the prescribed treatment

- Ability and expertise to ensure the processor understands the process, the defined critical factors and how to measure and control them

- Ability to evaluate potential deviations to determine whether a lot is a potential health hazard and make appropriate recommendations to ensure proper disposition (destruction, reprocessing, release)

With that, if we go back to our definition of a PCQI, is what defines the job adequate? Remember, there are two criteria for being recognized as a PCQI. Let’s examine these two criteria.

In 21 CFR Part 117.180 (c )(1), it states: “Job experience may qualify an individual to perform these functions if such experience has provided an individual with knowledge at least equivalent to that provided through the standardized curriculum.”

There are many persons in the industry who have the experience to do this task. However, I have found that most food processors have had their people attend and successfully complete a program on the development and application of risk-based preventive controls. The advantage of having experienced people be PCQIs is that they understand their limitations and know people in the industry who would have the necessary expertise to fill in-house gaps.

Now, the real issue is with some persons who are PCQIs because they have met the following criteria:

“A qualified individual who has successfully completed training in the development and application of risk-based preventive controls at least equivalent to that received under a standardized curriculum recognized as adequate by FDA.”

The concern with this route to becoming a PCQI is that there are no prerequisites for taking the class, nor is there any kind of screening of potential students. With my work in the industry, working with some companies and their PCQIs is a bit frightening. I will ask questions about their background, where they took the class and their industry experience. I get answers such as:

“I was a fine arts or English major.”

“I never took a HACCP class but took the PCQI program on the internet.”

“I am new to the food industry.” How new? “Two months.”

All I can do when I meet such persons and work with such companies is encourage them to focus more on education and training and try to bring more experienced persons on board. But I cannot say that I am very comfortable when I walk out the door.

In other words, is a 20-hour program over 2½ days that will now define a PCQI enough to allow you to sleep well at night as an owner or operator?

I suspect that the FDA had hoped that the PCQI would not only be able to complete the necessary training on the development and application of risk-based preventive controls, but also would have the necessary expertise based on knowledge, experience and training to be the food safety expert and process authority that the position demands. Unfortunately, this is not the case with all food processors.

Hopefully, the small number of processors with PCQIs who do not have the broad-based industry experience that others might have will not have food safety problems.

Companies that are in such a position would be wise to invest in further education and training for their PCQIs. Emphasize HACCP, sanitation, the Better Process Control School and a thermal processing workshop and have them attend a class where they can interact with others.

Don’t rely on distance learning. How the FDA will address companies that have less-qualified PCQIs remains to be seen.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!