Recall Rethink: Food Recall Vulnerabilities Exposed by the Cinnamon Applesauce Incident

August 5, 2024

Recall Rethink: Food Recall Vulnerabilities Exposed by the Cinnamon Applesauce Incident

August 5, 2024Video credit: Ianm35/Creatas Video+/Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

The recent lead chromate contamination incident in cinnamon applesauce pouches has continued to underscore critical gaps in our national food recall system. This incident illustrates the urgent need for modernizing food recall processes and enhancing data-sharing among federal, state, and local food safety and public health agencies to better protect consumers and ensure swift, effective responses to contamination events.

A Breach in Food Safety: Investigating the Contamination

On October 28, 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) posted the first notice of a new investigation. It began when the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) was investigating elevated blood lead levels in children. After ruling out potential lead sources in the children’s environment, the NCDHHS turned to a food item the affected children had in common: WanaBana apple cinnamon fruit purée pouches.1 What followed would send shock waves through consumers, food businesses, and the regulatory community: toxic lead chromate added to cinnamon for economic gain sickened over 500 children. The incident left many wondering how this could have happened and how we can prevent it from happening again.

Initial Investigations Lead to Prompt Public Health Alert and Product Recall

The contamination may have gone undetected if not for the astute work of NCDHHS investigators, who identified the apple cinnamon fruit purée connection, collected and analyzed samples, and quickly shared their findings showing extremely high levels of lead with the FDA.2 Shortly thereafter, a public health safety alert was issued, and product recalls commenced.

On October 28, 2023, Americans first learned of the danger contained in the popular children's snack when FDA issued a public health advisory.3 Parents and caregivers were instructed not to feed WanaBana apple cinnamon fruit purée pouches to toddlers and young children because of elevated lead levels. Parents whose children may have consumed the pouches were advised to contact their health provider about having their children tested for lead exposure.

The initial recall for the fruit pouches was announced two days later, on October 30, 2023.4 The recall was expanded 10 days later, on November 9, to include two private label brands, Schnucks and Weis.5 These recalls included 39 lots of pouches produced from January 2022 to October 2023, encompassing more than 20 months of production. Nearly 3 million recalled pouches were estimated to have been distributed nationwide.6

Elevated Lead Level Case Numbers Climb as Officials Trace the Source of Contamination

Unlike many foodborne illness outbreak investigations that see cases of illness climb until a source is identified and recalled, this investigation started with a small number of known illnesses that was quickly followed by a public health alert and product recall—only for the cases of elevated lead levels to soar once concerned consumers took their children in for lead testing.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!

By the time the second, expanded recall was announced, cases had jumped from the initial 4 to 22. The CDC issued a Health Alert Network advisory on November 13, 2023, emphasizing the harmful effects of lead in young bodies that are still developing.7 Children who had eaten the contaminated cinnamon applesauce had blood lead levels of between 4 and 29 micrograms of lead per deciliter, up to eight times higher than the federal reference level of concern.8 Those exposed experienced symptoms including headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, and anemia.7 There is no safe level of lead in children's blood. Even low levels of lead in the blood have been shown to have effects like learning difficulties, behavioral concerns, and irritability.9 Crucially, some children may not show any symptoms, or symptoms may not develop until much later, emphasizing the importance of getting children's blood lead levels tested.10

As FDA continued to investigate and trace the source of the lead contamination, enormous concentrations of lead were found in the recalled purée and sourced cinnamon. The lead level in the recalled purée was 2.18 parts per million (ppm)—200 times greater than the federally proposed action level in food intended for young children. Lead levels in the cinnamon supplied to the purée manufacturer were reported as high as 5,110 ppm. These extraordinarily high levels led FDA to suspect that a lead compound was intentionally added by the manufacturer of the ground cinnamon for economic gain.

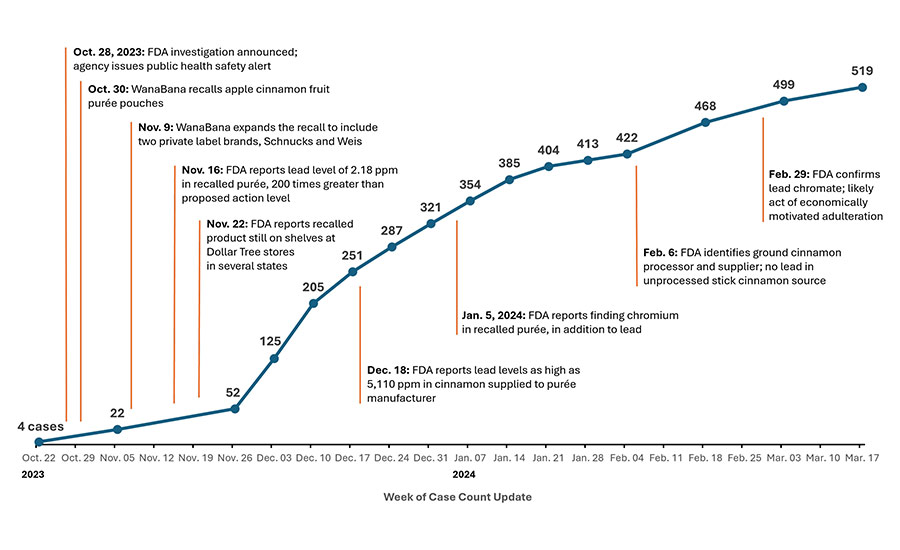

Meanwhile, the cases of lead poisoning continued to rise. There were over 100 cases by December 8, 2023 and over 200 cases two weeks later. The cases hit 300 at the start of January 2024. By the time the ground cinnamon processor and supplier was identified in early February 2024, there were over 400 cases. Figure 1 illustrates the rise in lead poisoning cases and key findings over the course of the investigation.

A Case Study Underscoring Our Broken Recall System

This outbreak was an unprecedented, economically motivated adulteration of a widely distributed food mostly consumed by young children; a food contaminated with a heavy metal that is particularly dangerous to those developing bodies. The scope and seriousness of this incident highlight significant gaps in how unsafe food is recalled in the U.S. and reaffirm the need to modernize the recall process.

The problems with the current way food recalls are carried out are well documented. The U.S. Government Accountability Office conducted two separate studies: one in 2004 after a deadly Listeria monocytogenes outbreak in deli meats and a large hepatitis A outbreak linked to green onions, and another in 2012 after the passage of FDA's Food Safety Modernization Act.11,12 In 2021, the Alliance to Stop Foodborne Illness published the results from a working group of food safety experts that was convened to outline how food recall processes in the country can be improved.13 In 2023, stakeholders shared many of the same concerns with the current way recalls are conducted and provided recommendations for food recall modernization during an FDA-hosted listening session.14

Persistent gaps in efficient and effective food recalls were prominent in the lead chromate in cinnamon applesauce contamination response, as outlined below.

Breakdowns in Recall Execution. A crucial first step in issuing a recall is determining the size and scope of the affected product. Many times, food companies will misidentify the full extent of likely contamination, only to issue a second (or even third), expanded recall. This multiple messaging causes confusion for consumers, as well as for downstream businesses. During the contaminated cinnamon applesauce incident, WanaBana issued an expanded recall 10 days after the initial recall. From the recalled lot code information, it appears that three production runs of the apple cinnamon purée for two private labels, Schnucks and Weis, were originally overlooked.

The next, equally crucial steps in recall execution are rapid communication to downstream businesses that received recalled product and swift action by those businesses to remove the product from commerce and from sale to consumers. In this incident, at least one large nationwide retailer, Dollar Tree, failed to promptly remove recalled cinnamon applesauce packages from its shelves. FDA reported that recalled products were still on store shelves in several states 23 days after the initial recall.15 FDA subsequently issued a warning letter to Dollar Tree for violating the law by continuing to offer the recalled food for sale.

Lack of Clear, Accessible Communication to the Public. Recall messages are disjointed, rely on outdated technology, and often fail to reach the consumers who have purchased the recalled food product. A recent nationwide Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO) consumer survey conducted by The Harris Poll found that 60 percent of Americans say they often have trouble figuring out if a product they have purchased is part of a recall.16

There is no single, integrated communication strategy; instead, the current system "puts the burden on consumers to seek out recall information" from government websites or social media sites that require members of the public to actively subscribe to them.17 In the cinnamon applesauce pouches incident, millions of recalled, shelf-stable, fruit purée pouches had been distributed across the nation for almost two years before the issue was discovered. These products were likely not only in the homes of consumers who were not easily reached by press releases, but also in secondary markets like food banks, resale shops, and online retailers that do not appear on official distribution lists.

The wording of recalls can also cause confusion, with consumers perceiving a "voluntary" recall as a recommendation, rather than posing a serious health risk.18 Both the initial and the expanded recall announcements for cinnamon applesauce products used the words "voluntary" and "voluntarily," which is the type of language that consumers may interpret to mean "minimal" risk.

Information-Sharing Gaps Among Federal, State, and Local Agencies. Foodborne illness outbreak investigations and recall events require close communication and coordination among federal, state, and local health officials and food regulatory agencies. Agencies follow up with downstream food manufacturers, wholesalers, distribution centers, and retail stores that received the recalled product and confirm that those businesses were notified and took proper action. Historically, these recall audit checks have been employed by state and local agencies differently than how they are used by FDA. State and local governments, which conduct most of the audits, use them as an immediate public health measure to ensure that recalled products have been removed from commerce. FDA, by contrast, has traditionally used the audits later, post-recall, to verify effectiveness; the agency has cited food businesses only 29 times since 2018 for lapses in recall plans under preventive controls for human food regulations.19

Those conducting the audit checks need timely, accurate, and complete lists of where and how much recalled product was distributed. These checks need to be coordinated to prevent duplication of efforts. Additionally, results of the audit checks need to be quickly collated, communicated, and analyzed to identify problems. While there have been concerted efforts to improve information-sharing among federal, state, and local agencies, many legal, technical, and operational obstacles remain.20,21 For example, a state agency must enter into a legal agreement to receive recalled product distribution lists from FDA. Even when such agreements are in place, the state is often prohibited from sharing that distribution information with local public health agencies. This often requires the state and local agencies to independently seek distribution information directly from the business initiating the recall, thereby diverting and delaying key resources from ensuring that unsafe products are not on store shelves. The good news is that FDA, AFDO, and the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture (NASDA) have recently agreed on fixes that address this issue, as well as other information-sharing challenges.

Inadequate Tools for Evaluating Recall Effectiveness. Unfortunately, there is no way for the public to know whether efforts to improve recalls are working because the effectiveness of audits and other assessment data are not published by FDA. The cinnamon applesauce recall was terminated on March 4, 2024, with no public indication of how many of the 2.99 million units were recovered or destroyed—or how well the company and the businesses that received the contaminated product executed the recall.

From Crisis to Resilience

There were numerous breakdowns in our food safety systems during this shocking contamination event, but there were also significant achievements. Public health and food safety specialists from different backgrounds, unaccustomed to working with one another, came together to solve a poisoning mystery that had likely gone undetected for over a year. NCDHHS staff deserves distinct praise for how its lead exposure investigators, epidemiologists, food regulators, and clinical and food laboratorians worked collaboratively and tirelessly to identify the source of the lead poisoning and alert the nation to this prevalent public health threat in the food supply.

A Call for Recall Modernization

The hundreds of children sickened from eating lead chromate-contaminated cinnamon applesauce has been a horrific and unprecedented event. This incident has exposed critical weaknesses in the safety of the supply chain and emphasized familiar deficiencies in food recalls. There is a shared responsibility between industry and regulators to modernize the U.S. recall system.

Necessary steps to modernize the nation's recall system include:

- Modernize and integrate outdated systems and processes: The current recall process is slow and inefficient, hampering swift action to remove unsafe products.

- Implement technological solutions: Technologies like blockchain-enabled real-time traceability, advanced bar codes that contain additional information, and smartphone alerts can improve recall speed and effectiveness.

- Harmonize and improve communication strategies: Clear, accessible communication is of the utmost importance. A modernized communication strategy would utilize current technologies and employ targeted outreach to affected populations.

- Enhanced data-sharing: Improved data-sharing among regulatory agencies and with industry is needed to coordinate recall response efforts and improve assessment of recall effectiveness.

- Public-private collaboration: Industry and regulators should collaborate on innovative recall solutions to maximize consumer safety.

Food is very different from other FDA-regulated commodities. Simply put, each piece of produce (e.g., apple, onion, cantaloupe, etc.) does not and will never have a unique identifier like a prescription drug or a medical device does. This needs to be recognized with regulations, policies, and procedures focused on the unique and complex food system. Regulators, food businesses, and Congress are urged to use this crisis as a catalyst for systemic change that builds a more robust, transparent, and resilient food system.

References

- Arthur, K. "How NC health investigators discovered applesauce was poisoning children." WRAL News. January 15, 2024. https://www.wral.com/story/how-nc-health-investigators-discovered-applesauce-was-poisoning-children/21238040/.

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. "NCDHHS Urges Caution After Reportable Lead Found in WanaBana Brand Apple Cinnamon Puree." October 28, 2023. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/2023/10/28/ncdhhs-urges-caution-after-reportable-lead-found-wanabana-brand-apple-cinnamon-puree.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "FDA Advises Parents and Caregivers Not to Buy or Feed WanaBana Apple Cinnamon Fruit Puree Pouches to Toddlers and Young Children Because of Elevated Lead Levels." October 28, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/food/alerts-advisories-safety-information/fda-advises-parents-and-caregivers-not-buy-or-feed-wanabana-apple-cinnamon-fruit-puree-pouches.

- FDA. "WanaBana Issues Voluntary Recall of WanaBana Apple Cinnamon Fruit Purée Pouches Due to Elevated Lead Levels." October 31, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/wanabana-issues-voluntary-recall-wanabana-apple-cinnamon-fruit-puree-pouches-due-elevated-lead.

- FDA. "WanaBana Recalls WanaBana, Weis, and Schnucks Apple Cinnamon Fruit Purée Pouches & Cinnamon Apple Sauce Due to Elevated Lead Levels." November 9, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/wanabana-recalls-wanabana-weis-and-schnucks-apple-cinnamon-fruit-puree-pouches-cinnamon-apple-sauce.

- FDA. "Enforcement Report 93340." November 8, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/ires/index.cfm?Product=204034.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "Health Alert Network (HAN): High Blood Lead Levels in Children Consuming Recalled Cinnamon Applesauce Pouches." November 13, 2023. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2023/han00500.asp.

- CDC. "CDC Updates Blood Lead Reference Value." April 2, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/lead-prevention/php/news-features/updates-blood-lead-reference-value.html.

- Aleccia, J. "Parents of children sickened by lead linked to tainted fruit pouches fear for kids' future." AP News. December 20, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/wanabana-apple-cinnamon-lead-poisoning-fruit-pouch-86c32266e010843d0c9ad3340ccae319.

- Lovelace Jr., B and K. Abou-Sabe. "Months after applesauce recall, parents remain in constant fear about possible long term effects." NBC News. February 28, 2024. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/wanabana-applesauce-recall-lead-poisoning-long-term-effects-kids-rcna140058.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). "Food Safety: FDA's Food Advisory and Recall Process Needs Strengthening." July 26, 2012. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-12-589.

- GAO. "Food Safety: USDA and FDA Need to Better Ensure Prompt and Complete Recalls of Potentially Unsafe Food" October 7, 2004. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-05-51.

- STOP Foodborne Illness. "Collaborative Plan to Achieve Consumer-Focused Recall Modernization." July 2021. https://stopfoodborneillness.org/customer-focused-recall-modernization/.

- FDA. "Public Meeting: Modernizing Recalls of FDA-Regulated Commodities." September 29, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/regulatory-news-stories-and-features/public-meeting-modernizing-recalls-fda-regulated-commodities-09292023.

- FDA. "Investigation of Elevated Lead & Chromium Levels: Cinnamon Applesauce Pouches (November 2023)." April 16, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/investigation-elevated-lead-chromium-levels-cinnamon-applesauce-pouches-november-2023.

- Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO). Raw data from Harris On Demand Food Safety Study. Published online December 2023.

- Coffman, V. and M.D. Baum. "Modernizing Recalls is a Must for Consumer Safety." Food Safety Magazine. June 7, 2022. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/7780-modernizing-recalls-is-a-must-for-consumer-safety.

- Ablan, M., K. McFadden, and M. Jhung, et al. "A Qualitative Evaluation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Risk Communication Methods during Multistate Foodborne Outbreaks." Food Protection Trends 41, no. 6 (2021): 547–554.

- FDA. “FDA Data Dashboard: Inspections and Compliance Actions, 2018–2023.” Accessed May 23, 2024. https://datadashboard.fda.gov/ora/index.htm.

- PFP Surveillance, Response, and Post-Response Workgroup. "Best Practices for Improving FDA and State Communication During Food Recalls." Partnership for Food Protection. 2021.

- PFP Surveillance, Response, and Post-Response Workgroup. "Recall Integration Partnership Pilot (RIPP) Outcome Statement." November 2022. https://web-fs.s3-fips-us-gov-west-1.amazonaws.com/PFP/assets/File/PFP%20SRPR%20RIPP%20Project%20Outcome%20November%202022.pdf.

Carrie Rigdon, Ph.D., is Research Director at the Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO). She leads and assists several projects in research question development, effective data collection, detailed data analysis, and the publication of findings. Prior to joining AFDO, Dr. Rigdon worked at the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, initially in helping to develop Minnesota's Food Emergency Rapid Response Team, coordinating foodborne illness outbreak and traceback investigations; she later served as the Operations Manager and the interim Assistant Division Director for food and feed safety. Rigdon earned her M.P.H. degree in Epidemiology from San Diego State University and her Ph.D. in environmental health (with a focus in foodborne illness) from the University of Minnesota.

Steven Mandernach, J.D., is the Executive Director of the Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO). Prior to becoming Executive Director in 2018, he was the Bureau Chief for food and consumer safety at the Iowa Department of Inspections and Appeals. Mandernach is a past President of AFDO. He has also served as the Chair and Co-Chair for the Manufactured Food Regulatory Program Alliance. Mandernach has co-authored many articles and book chapters related to retail food safety, foodborne illness detection, and the integrated food safety system. He is also a frequent contributor to food trade publications. Mandernach has a J.D. from Drake University Law School. He has also completed graduate work in food safety at Michigan State University.