Comprehensive training is key to food safety efforts

By offering workers training and coaching, processors can ensure food safety goals are met

A combination of technology-based training and on-the-floor coaching can help processors ensure their employees are getting the most out of training. Source: Alchemy Systems

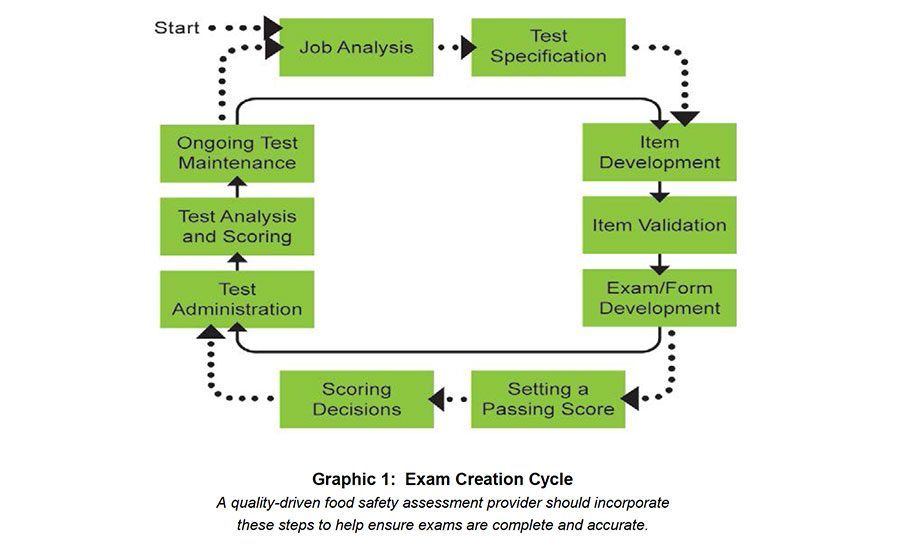

An illustration of Prometric's exam development cycle. Source: Prometric.

The increased use of tablets and other smart devices allows food processors to not only manage their operations, but offer new training options for employees. Source: Alchemy Systems

The ink cartridges on the labeling line needed to be changed, but the employee who knew how to do it was retiring soon.

One portable video camera later, the company had a solution that wouldn’t walk out the door when the employee did. By mounting a GoPro camera to his hat and recording the steps to the process, the employee provided a convenient, reusable training tool that gave the company a way to ensure that other employees knew exactly what steps to take and how to perform each one.

Not every training challenge can—or should—be solved this way. But what this example shows is that regardless of exactly what you’re training operators on, the training has to be comprehensive, understandable and usable, says Raj Shah, chief marketing & strategy officer, Alchemy Systems.

“You want to ensure your operators have two things,” says Shah, “the knowledge of what to do and the confidence to do it right when that action happens.”

To do this, processors need to evaluate a couple things before deciding on a training program. The first one is relatively easy: identifying what you know and don’t know. The second is a little trickier: identifying what you don’t know you don’t know. Both of these steps require an honest assessment of where you are right now, where you want to be in the future and how you want to get there. They also require not just input from the top down, but from the bottom up. By checking all of these boxes, processors can ensure that their training is giving their operators the tools they need to succeed, while still meeting food safety requirements.

What you know

Food processing—much like any kind of manufacturing—tends to be a lagging adopter of new technology. Systems require so much money and effort to be put in place that when you find one that works, you stick with it for as long as you can.

This attitude has made sense for a long time, because big, expensive pieces of equipment are built to last. You don’t buy a dryer with the expectation that you will have to replace it in two years.

But the pace of change in equipment, software and interconnected devices has accelerated so much recently that food manufacturing plants aren’t just islands of technology anymore. Instead of three separate parts of the production line being three separate silos of information, the ability to share data across equipment and use that data to inform decisions is offering processors a lot more flexibility in how they do things.

“You’re not just doing something in isolation anymore,” says Brandon Murphy, professional services manager, Cat Squared. “You’re going to do something, and then that data may also be merged with data coming from PLCs on machines.”

Connected machines offer a big benefit from data, but they also can free up operators to move around the plant floor. While someone may have previously had to stay in one place during an entire shift, equipment that can send alerts to a tablet or smartphone allows a worker to be away from that certain spot in the production process until it’s time for a manual task to be performed. When the worker is needed at a particular location to do a particular task, an alert can be pushed to a device to call him or her back to that station. Or, if something goes wrong, an alarm can quickly alert the worker to the issue and stop the production process at the point of failure.

This allows for more flexibility in defining operators’ roles, but it also means that they can’t just be trained on one job anymore. They have to be given a way to understand all the different roles they might fill during a shift, which means adapting training to be flexible and malleable, depending on the workers participating in it and what roles they might fill.

Brian Fortney, global business manager, customer training, Rockwell Automation, says that this flexibility requires a change in mindset when it comes to deciding what training and preparation you need for operators.

“How do you as a manufacturer, how do you as a food processor, think about your workforce in your productivity efforts?” he asks. “It’s much more impactful to think of it in terms of skills on the floor, and that’s something that I don’t think is always thought of in the design process.”

What you don’t know

Connected machines offer a lot of advantages, but there can sometimes be some challenges in getting people on board with the idea of them. For one thing, says Murphy, sometimes, processors want to know why they don’t have an Internet of Things.

“You do have an Internet of Things,” he says. “You have the pieces for it, and you have the people to run it.”

So, step one is often understanding that you may need more in-depth knowledge of what exactly your equipment can and can’t do. Obviously, the manufacturer provides a lot of that information, but another valuable resource for understanding what your equipment does, how it does it and how you can get what you want out of it is the people who operate it.

“When I walk into a room, and there’s an operator present, I’m like, ’OK, these people are ready to go,’” says Fortney.

By including operators instead of just upper management, you get a more comprehensive picture of what you don’t know, because the people who are doing the job every day have a wealth of knowledge about how systems operate. They’re also the ones who are often coming up with workarounds or shortcuts that help improve efficiency—without sacrificing quality and safety.

Once you’ve identified what you don’t know, you can use that to help shape your training goals. While it may sound odd to use “what we don’t know” as the basis for training, the key thing to remember is that the training should help provide answers to “what we don’t know.” For example, if your production supervisors and operators aren’t taking advantage of what your equipment can do, what’s the point in spending the money on extra features? Or, to put it another way, you’re probably going to have to spend the money on those features as they become standard, so why not take advantage of them?

When training goals are defined, an assessment helps ensure that operators are actually getting what they’re supposed to out of the training, says Holly Dance, vice president, global account management, Prometric.

“You have to be able to measure the effectiveness of your training, and the way you do that is through an assessment,” says Dance. “You can’t train someone and hope for the best.”

Assessing the assessments

The rapid pace of change isn’t just a challenge for processors that are trying to ensure their training is up to snuff. It’s a challenge for the companies that build and administer training and assessments as well.

Prometric regularly reevaluates what skills need to be assessed to ensure its testing is up to date, says Dance. The company annually studies whether its testing is in line with the latest food codes, food safety standards and best practices and consults with subject matter experts across the industry. These steps allow Prometric to ensure it is offering testing and assessments that are up to date, regardless of how quickly the industry is changing.

“We go through a pretty rigorous cycle to make sure that the exam is up to date,” says Dance.

Another challenge for the test administrators is how people are taking the test is changing, says Jana Von Bramer, Prometric senior vice president, global marketing.

“It used to be paper and pencil,” says Von Bramer. “Then, it became computerized; you’d have to go to a test center. Now, you have to go back into onsite testing, and our [personal] technology is enabling that.”

The upside of this is that the explosion in smart devices offers processors a couple of different ways to take advantage of mobile options. The first is that, as Von Bramer points out, operators can take all sorts of different tests straight from a tablet or a smartphone, meaning they don’t have to travel off site to take an assessment.

Another benefit is that processors can offer on-the-fly training as needed. With connected equipment allowing for more flexibility in operator roles, operators don’t just have to stay in one place for their entire shift. But if an operator is covering for someone or moving into a new role, he or she may need training on new equipment or processes.

One new way of handling that is through video training, says Shah. Operators can watch a video of how a process is supposed to work, then answer questions at the end to ensure they understand the key points. This can also be used in conjunction with a trainer or experienced operator walking an employee through a process, then keeping track of which areas might need more training or assessment.

Using video and other technologies doesn’t have to be formal training, as Shah pointed out with the anecdote mentioned earlier about an employee recording himself changing ink cartridges. Video or even still shots can be used to help show employees what to do instead of just telling them.

How training can fail

Any training program is only as good as its execution, and part of that execution is following up on the training to make sure that it’s meeting its goals. Conducting training and then leaving employees to their own devices is not a recipe for success, especially in an industry that has a high turnover rate. In addition to that, the generation entering the workforce is tech savvy and more comfortable with interactive or video training than they are with paper and pencil assessments. That can lead to a disconnect for new employees between traditional training and assessment methods and how they are used to learning.

For the past five years, Alchemy has surveyed the industry to find out why and how training works and doesn’t work for food processors. The three most common answers from this year’s survey (Global Food Safety Training survey) about why training fails will probably come as no surprise:

- Bad habits

- Prefer doing things the old way

- Followed other employee’s direction.

If you’re looking for a one-sentence summation of those three points, it might be something like “This is the way we’ve always done it.” Changing how something has been done is hard, and it won’t be accomplished by just having employees sit through training and then never following up.

One important thing to keep in mind, Fortney says, is that the attitude of having always done something one particular way probably has more to it. He says it’s natural for operators to have concerns or hesitation about a new way of doing their job, but offering an honest, comprehensive explanation as to why their role is changing and how they can successfully perform their new tasks can help overcome their trepidation.

Adding to the complexities of successful training is what respondents have listed as the No. 1 challenge every year that Alchemy has conducted the survey: Scheduling time for training.

Supervisors and team leaders can help fill an important role by being part of ongoing training that tackles process and equipment training in smaller pieces. While new employees or employees moving into new roles may still go through formal training, being coached on the production floor by an experienced employee can help reinforce what is learned in training and prevent mistakes.

“We’re starting to see more and more of the on-the-floor observation and coaching,” says Shah. “That’s really important, because if you’re not having that interaction, and you’re just relying on the guy next to you telling you what to do, that can lead to consistency issues.”

For more information:

Brandon Murphy, Cat Squared,

501-328-9178, brandon.murphy@catsquared.com

Raj Shah, Alchemy Systems,

512-637-5188, raj.shah@alchemysystems.com

Brian Fortney, Rockwell Automation,

440-646-3434, bfortney@ra.rockwell.com

Holly Dance, Prometric,

847-572-0550, holly.dance@prometric.com

Jana Von Bramer, Prometric,

443-455-6088, jana.vonbramer@prometric.com

This article was originally posted on www.foodengineeringmag.com.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!