Food Safety

The importance of preventive controls

Preventive controls are a must for processors to meet safety goals

Inspecting food under the preventative control system is not process centric, but risk based.

Photo courtesy of Getty images

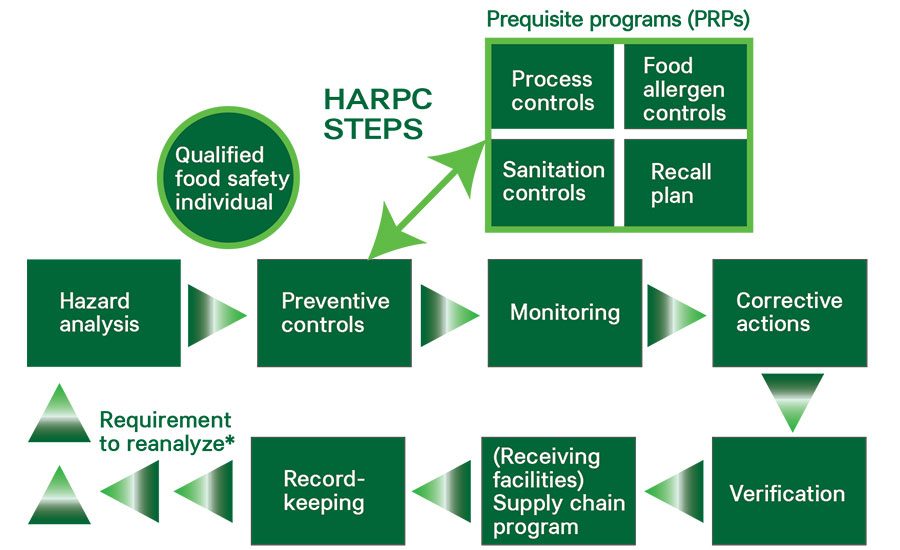

An updated Preventive Controls diagram shows the procedural steps for setting up an FSMA-conformant system. Begin with a hazard analysis, follow with a Preventive Controls step (which includes PRPs), then monitoring, corrective actions, verification, supply chain program, recordkeeping and, finally, a requirement to reanalyze. *The reanalysis must occur every three years or when a significant change is made to the process or any of the steps.

Registrar Corp’s www.FDAMonitor.com software assists suppliers in meeting the requirements of their supply chains.

Photo courtesy of Registrar Corp.

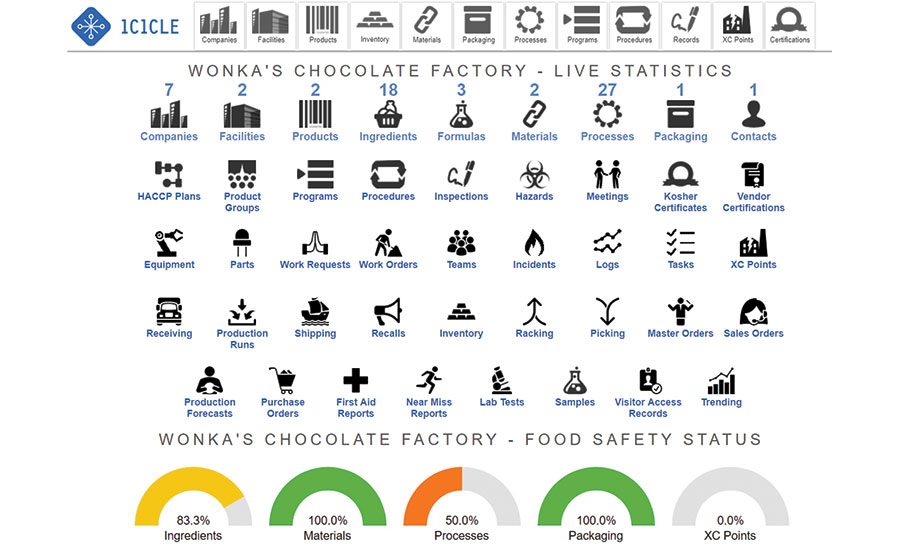

Icicle keeps operators in control, making compliance easy.

Photo courtesy of Icicle Technologies

Trace Register’s Full-Chain Traceability and TR+ Analytics with CMCA puts the power of data to work, providing real-time risk assessment back to the source and an integral way to implement continuous monitoring and improvement.

Photo courtesy of Trace Register

What’s in a name … or acronym? Take HARPC, for example. Technically, it refers to “Hazard Analysis and Risk-based Preventive Controls.” And it’s a major part of FSMA, or at least it was.

Initially, FDA used the acronym, but now, no longer recognizes it, according to Radojka Barycki, technical training manager for SCS Global Services. The Food Safety Preventive Controls Alliance (FSPCA) training materials and FDA regulatory documents no longer contain the term.

Instead, HARPC has been supplanted simply with “Preventive Controls,” either for human food or animal food, which is much easier to remember and rather self-descriptive. But the terms mean the same thing.

Article Index:

Regardless of the name, the framework it provides is meant to aid in process control, not only to make food products safer, but also more consistent in quality. Also, Preventive Controls, ideally, can help improve performance and throughput.

HACCP vs. Preventive Controls

“HACCP is process-centric,” says Steven Burton, CEO and founder of Icicle Technologies, a provider of a comprehensive food production management system. “HACCP focuses on the critical control points [how to control a hazard or multiple hazards] at each process step depending on the hazards associated with that process.”

Started decades ago in the US space program, HACCP is a venerable protocol today and is practiced, for example, by USDA manufacturers, seafood producers, juice processors and other processors not covered by the FSMA Preventive Controls rules.

Instead, Preventive Controls is not process-centric, but risk-based. And its principles are not new concepts.

“They are taken from internationally recognized standards established in the development of HACCP, but are broader in scope,” says Carey Allen, director of food safety certification at NSF International.

The outcome of a facility’s hazard analysis is dependent upon the extent of implemented prerequisite programs, or PRPs, which are practices, such as sanitary design, housekeeping and sanitation programs, intended to prevent hazards before they occur, says Allen. The PRPs are not required to be regularly monitored and managed in the same way as a CCP (critical control point). The PRPs essentially set the stage for the stable process upon which the CCPs are identified. With well-developed PRPs, it is possible that a site may determine that no CCPs are necessary.

“[Preventive Controls] builds on decades of advancements in food science and is the epitome of the adage: ‘An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,’” says Bracey Parr, Registrar Corp’s regulatory specialist & project coordinator, PCQI. “[Preventive Controls’] preventive approach takes activities traditionally categorized as PRPs, such as sanitation schedules, and elevates them to the status of ‘control’ due to their importance in preventing hazards.”

Preventive Controls requires defining a control not just for known hazards in the process, but also considering the likelihood of severe hazards that are not normally present, but could occur, and defining controls for those as well. In short, says Allen, with HACCP, CCPs are identified on a stable process made possible through PRPs. With Preventive Controls, the control aspect of the PRP must be included and managed as a preventive control.

The Preventive Controls rules do not apply only to the manufacturing process itself, says SCS’s Barycki. They are broader regulations containing four areas of focus to consider when performing the hazard analysis.

These areas are:

- Supply chain: receiving of ingredients and shipping of finished goods

- Process: the manufacturing process

- Allergens: receiving of ingredients, manufacturing and shipping of finished goods

- Sanitation: all sanitation functions applicable to processing, specifically for environmental pathogens that could be reintroduced in RTE foods, if not monitored closely.

HACCP focuses on the manufacturing process only and on the assignment of critical control points within the food/beverage manufacturing process, adds Barycki. The Preventive Controls rules are a more holistic approach to food safety, because they require that food/beverage manufacturers identify and implement controls based on a risk assessment for hazards that can be introduced during receiving, manufacturing, shipping and sanitation processes. They also place an emphasis on allergen cross-contact risk assessments and controls. Allergen cross-contamination is the number one cause of recalls in the US.

In addition to the Preventive Controls rules for human and animal foods, FSMA addresses imported food products (foreign supplier verification program [FSVP]), produce safety (Produce Rule) and food transport (Sanitary Transportation Rule), which complement the holistic approach that is required in the manufacturing of food and beverage products, says Barycki.

Preventive Controls: Eyes wide open

In what ways can Preventive Controls improve a food and beverage processor’s approach to food safety? Warren Gilbert, partner, FSS Corp.—Food Safety Specialists, suggests that Preventive Controls adds a higher level of food safety, requiring processors to do additional checks and balances (verification/validation). While performing these steps requires more effort, it’s worthwhile, because it also provides a higher level of accountability, transparency and brand name protection, which has true benefits in today’s highly competitive world.

It’s hard to get away from the term, holistic, because it might be the best one-word description of how processors should think about Preventive Controls. Food safety focuses on procedures for handling, preparing and storing food in a way that best reduces food safety events, says Dr. Dag Heggelund, executive vice president and chief technology officer at Trace Register, a provider of food safety software.

“[Preventive Controls] enables companies to proactively assess the hazard events in a holistic supply chain view.”

Preventive Controls requires a different learning approach than HACCP. Neal Mays, food safety specialist at Safe Foods Corporation, a supplier of antimicrobial chemistries, likens the learning of Preventive Controls to Bloom’s Taxonomy pyramid, a means of categorizing critical thinking skills. Basic skills like learning, defining and labeling are at the bottom, while more challenging skills like creation, evaluation and justification are at the top.

Similarly, says Mays, under Preventive Controls, the food safety focus must shift from the more basic procedures of identifying and categorizing hazards and critical control points to evaluating the entire process and justifying why safety parameters are included in safety plans. Done well, this forces management to pressure test the rationale surrounding preventive control measures and implement changes that may better serve the facility’s overall food safety goals—and better protect a processor’s brand in so doing.

“Unlike HACCP, whose principle focus is on what happens inside a food plant, FSMA expands that focus by encompassing the entire food chain,” says Dan Bernkopf, SafetyChain vice president food safety and quality applications. “Where historical HACCP may have only looked at the risk associated with an ingredient, FSMA also looks at the ingredient’s supply chain risks, including country of origin, and any risks associated with ingredient and specific supplier’s storage, transportation and any historical non-compliances.”

With FSMA’s Preventive Controls, processors are forced to implement the controls needed to prevent hazards that aren’t covered under HACCP, adds Icicle’s Burton. These hazards include intentional adulterations and natural toxins, while keeping track of hazards associated with processing steps, such as the specific temperature required for kill steps.

Take, for example, performing a risk assessment on apple juice, says SCS’s Barycki. Patulin is a chemical hazard likely to occur and can have long-term, adverse health effects when consumed at levels higher than 50 ppb. This naturally occurring toxin is produced by Aspergillus sp. (mold). Patulin is federally regulated; apple juice is not allowed to have more than 50 ppb of patulin. Under HACCP, receiving the Certificate of Analysis (COA) for apple juice containing the results for patulin is considered an HACCP foundational or prerequisite program, “Receiving.” However, from the Preventive Controls’ perspective, based on risk analysis and significance, the receiving of the COA for apple juice could become a supply chain preventive control.

Can Preventive Controls improve food quality?

While the Preventive Controls rules weren’t necessarily set up by FDA to improve food quality, it seems that if processors are really paying attention to the big picture—improving food safety through the entire supply chain—then food quality would also benefit from this effort.

“[Preventive Controls] has the potential to support a food quality system; however, in creating the program, the processor will have to exchange the food safety aspects with quality aspects,” says FSS Corp.’s Gilbert, “that is, the processor will have to define ‘key indicators,’ such as net weights, color, odor, etc. vs. kill steps, labeling, etc.”

“Food quality and food safety can be viewed as a measure along a single continuum,” says Trace Register’s Heggelund.

A Preventive Controls system with tighter controls can be used to proactively predict food quality issues in the same manner it can proactively predict food safety issues.

“I would expect improvements in food quality associated with well-executed [Preventive Controls] protocols,” says Safe Foods’ Mays.

Like pathogens, spoilage organisms proliferate when conditions favor their growth, and antimicrobial chemistries effectively reduce numbers for both. For example, cross-contamination of spoilage and pathogenic organisms may be readily observed when washing fresh or minimally processed produce. Similarly, Mays notes that Preventive Controls practices also need to be applied to processing equipment—both in terms of maintenance and sanitation.

Mays points to an example involving maintenance and quality. In sliced fruit, metabolic reactions negatively associated with cuts/wounds include discoloration, texture changes and accelerated ripening. Studies have shown shelf life may be lengthened by simply keeping knives and other cutting edges sharp. Routine maintenance practices could be easily included in facility Preventive Controls protocols.

Lessons learned in food safety can be applied to quality as well, says SafetyChain’s Bernkopf. The same requirements for the organization and maintenance of product quality compliance documents, inspections and data apply to quality.

“On any normal production day, when you’re running a food manufacturing plant, you are spending more time on food quality than on food safety, unless you have a food safety issue you are addressing,” adds Bernkopf. “Therefore, your food quality plan and system must be equally as competent and robust as your food safety systems.”

The Preventive Controls rules requirements, like HACCP, are not sustainable unless the foundational PRPs supporting the system are implemented, says SCS’s Barycki. These foundational programs (e.g., preventive maintenance, sanitation, calibration, etc.) are closely related to preserve not only the safety of food, but also its quality attributes. For example, if a thermometer measuring temperature in a cooler is not calibrated, and the temperature falls outside an acceptable range, the product could spoil, causing losses due to quality issues.

The Preventive Controls’ preventative approach encourages food companies to adopt comprehensive monitoring during every step of the food production process, says Icicle’s Burton. When a company chooses to use a food safety system to comply with preventive control regulations, it can then use the same system to ensure high quality.

For example, adds Burton, undercooked poultry is a food safety issue. HACCP and Preventive Controls standards require that minimum internal temperatures are achieved during cooking. The same system can be used to ensure the poultry is not overcooked, which is a quality issue.

Freezer burn, however, is a food quality issue rather than a food safety issue. With a comprehensive software system, it’s easy to control inventory, as well as temperature, to ensure that products don’t languish in the freezer, which causes freezer burn. Product and production parameters can be controlled in both directions to achieve excellence for both food safety and food quality, says Burton.

Can risk assessments improve quality? Food and beverage processors should go through the process of performing risk assessments and reevaluating all foundational programs to determine if they need to be included as Preventive Controls or kept as PRPs, says Barycki. These reviews will likely create a higher awareness, not only relative to food safety but also quality.

“I strongly believe that increasing food safety awareness also increases quality awareness, as these attributes usually go hand in hand,” adds Barycki.

The same principles for evaluating and controlling food safety risks are directly applicable to defining and controlling quality requirements, says NSF’s Allen. For both food safety and food quality, the hazards categories must be defined. In a quality management plan, the quality characteristics requiring control must be defined using industry standards, customer standards or internally defined product attribute specifications. For example, piece size, shape, color and weight may be defined as the key quality criteria for a product such as breaded fish portions. The processor must know what operational or supplier controls are necessary to control these characteristics and what hazards may occur in the process to throw off that control. Calibrating, monitoring and rewarding compliance of the various breading suppliers may reduce variation in the coating color. Operator training and preventive maintenance of the cutting blades may improve portion weight and shape consistency. Continuous process control data collection and tracking may assist with reducing package weight variation.

By understanding the key food safety and quality characteristics, how they are controlled and what events may negatively affect control, the processor can employ methods to drive consistency and reduce the likelihood of process errors, adds Allen.

Software systems’ role in training, food safety and quality

“I believe software applications that are applied to recordkeeping, testing and training are good tools for the creation and implementation of food safety plans,” says SCS’s Barycki.

Food safety and quality management systems, such as those within the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) schemes, provide the framework for recordkeeping, training hazard analysis (food safety), prerequisite programs, etc., which are required in the Preventive Controls rules. Software applications are aimed to eliminate or reduce paperwork and actively manage food safety and quality. Software programs can connect to computers and track data, making analysis easier and, therefore, the management of food safety and quality more efficient, adds Barycki.

Until recently, the cost of collecting the data required for an effective Preventive Controls system had been viewed by many as a major barrier to adoption.

“The seafood industry is not the first industry to address quality issues,” says Trace Register’s Heggelund. “Manufacturing has led the way and has demonstrated that integrated, proactive quality systems are not a ‘cost center,’ but improved quality systems through proactive quality management are in fact ‘profit centers.’”

The first hurdle is for food and beverage processors to appreciate that with today’s technology, the cost of low quality is far greater than the cost of achieving high quality.

“This was not the case until new technologies, such as Trace Register’s TR+ Analytics with CMCA [continuous monitoring/continuous auditing], dramatically lowered the cost of achieving high quality through the use of proactive, risk-based controls,” says Heggelund.

“There are strong synergies between food safety and food quality,” says SafetyChain’s Bernkopf.

Hazard analysis methods can be employed for quality risk assessments, as well as product specifications and attributes.

“As is true for food safety, so is true for food quality: You must say what you do, do what you say and document all in records,” says Bernkopf. “With paper-based records, your first issue is: Am I compliant in food safety? If that answer is yes, the next question is: Am I compliant in food quality? If that answer is yes, in a traditional paper-based way of managing your programs, you just take all of that paper data/records and file it away. But if you are tracking your programs with a food quality management system, you can go beyond compliance with analytics and use that data to improve your processes in food safety and quality assurance.”

Quality management and food safety software also serves to help with food safety and quality training.

“Icicle is built to educate, as well as implement food safety programs,” says Burton. “Our intuitive system creates a virtual model of the way a business actually runs.”

Users can be guided through regulatory procedures, such as HACCP or Preventive Controls, in how these regulations relate to their facilities and their processes. Processors learn about regulations step by step as they set up their Icicle account and maintain it day to day, adds Burton. At the end of each day, all information is updated, synced and ready to go for audits and inspections. Icicle is built so that all compliance and quality standards help companies achieve the same goal, in the same place. Following regulations (e.g., HACCP and Preventive Controls) is built into the software and clearly laid out for users.

“The more people use Icicle, the smarter it becomes,” adds Burton. “We’re collecting large quantities of anonymized data that assists with food safety education and training. As our database grows, we can mine this data to provide new features, such as Smart Hazard Suggestions, which suggests common hazards associated with process steps, ingredients, materials, etc. This feature helps experienced food safety professionals build their plans faster and more efficiently.”

Other tools can help

Statistical Process Control (SPC) software, an analytical tool used in quality and continuous improvement, is a good example of the integration of data collection, paperwork reduction/elimination and data analysis, which is summarized utilizing readable charts for the review of records in a quality management system (QMS), says Barycki. Similar software applications are already developed for food safety data analysis.

Quality and consistency are what SPC is about. Giorgio Foods, a maker of frozen pizzas, was having a tough time with over-weights and inconsistent topping fills. Paper records had scattered, inaccurate data, and there was a lack of timely information that could pinpoint production problems.

Plus, no one had a clear understanding of the problem; 12-oz. pizzas might weigh 14 oz., and toppings were either wrong or overfilled. It often took days to get weight data, and there were bins of trashed product spilling into the aisles and walkways.

“We were not a waste reduction culture,” says Dan Wadyka, Giorgio assistant director of quality.

But after implementing Hertzler Systems’ GainSeeker SPC software and getting entirely off paper, the pizza maker was able reduce its waste and overfill by 70 to 80 percent in six weeks.

“GainSeeker has given us the visibility we need to reduce waste and product giveaway,” says Wadyka.

Evan Miller, Hertzler Systems president, will be the first to say that while SPC software may solve quality problems well, it doesn’t necessarily handle Preventive Controls.

“A product like ours is designed to make it easy to collect, visualize and act on data. Having that data at your fingertips is really important and valuable. At the same time, we don’t walk users through a risk assessment. We assume that work has been done and is probably in some collection of documents or spreadsheets,” Miller says.

There are many software programs available for SPC that can collect live process data automatically or manually, track it and use it to adjust the process within control limits if engineered this way, says NSF’s Allen. While these programs serve to reduce hard-copy paperwork, they also make it possible to analyze the data, along with financial data and supplier quality data, to track correlations in quality scores with process efficiency or defect rates. This can help pinpoint quality parameters that require tighter control or interactions between raw materials that were not previously apparent.

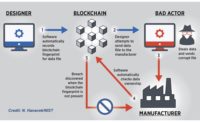

Speaking of suppliers, Registrar Corp has created a site, www.FDAMonitor.com, to help processors with supply chain-related issues. According to Parr, the system allows users to:

- Assess FDA compliance history

- Monitor FDA compliance status

- Approve suppliers

- Produce monthly reports

- Receive alerts when there is a change in status.

As opposed to document storage and management systems, FDAMonitor.com is specifically designed to gather and push vital information to manufacturers and importers to help them comply with requirements in Preventive Controls supply-chain requirements and the Foreign Supplier Verification Program.

What a processor should already be doing

The Preventive Controls rules include what a processor should already be doing to run a sustainable business, says NSF’s Allen.

Understanding your products, your process, your customers and consumers—and how to control risk in any part of the supply chain—is at the heart of Preventive Controls. Having a system to document this understanding, to collect data for analysis and to make informed decisions will improve food safety and quality proactively, concludes Allen.

For more information:

SCS Global Services, www.scsglobalservices.com

NSF International, www.nsf.org

Registrar Corp, www.registrarcorp.com

Icicle Technologies Inc., www.icicletechnologies.com

FSS Corp., www.foodsafetyspecialists.com

Safe Foods Corporation, www.safefoods.net

SafetyChain Software Inc., www.safetychain.com

Trace Register, www.traceregister.com

Hertzler Systems, www.hertzler.com

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!