Supply Chain Management: A Year in Review

To understand supply chain disruptions in a more systematic way, broader scenario planning and more rigorous work processes are needed

Video credit: Golden Sikorka/Creatas Video+ / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

We seem to be in the golden age of supply chain management. New appreciation has arisen for the fragility of our networks and the complexity of keeping a company running. So, too, has arisen an unending stream of different and more impactful supply chain disruptions. The past two years have been unprecedented, but to the point that radical supply chain disruptions are now becoming precedented.

The disruptions are so extreme and so varied that it has become necessary to reset our expectations and the scope of our management systems. We need a more systematic way to classify and understand supply chain disruptions. New, broader scenario planning is needed. More rigorous work processes are also needed, so that we are not just chasing from one fire to the next.

By John W. Spink, Ph.D., Michigan State University and Food Fraud Prevention Think Tank

Supply Chain Management Background

My formal expansion into supply chain management, from focusing mainly on food fraud prevention, started in September 2019 when I moved to the Michigan State University (MSU) Department of Supply Chain Management within the University's Business College. I revamped the Introduction to Supply Chain Management undergraduate course required for all business school students. My 15 years of developing and teaching applied business in graduate courses at MSU, combined with my broad supply chain-related work experience at Chevron Corporation, was an excellent fit for this task. I brought a holistic approach to the introductory concepts that used hot topics to expand the student experience.

When we consider hot topics in supply chain management, we start with the impacts of COVID-19, then the Ukraine–Russia conflict, and now inflation. Additionally, we were already tracking the trends of artificial intelligence, data analytics, autonomous vehicles (in a warehouse and on the highway), electric cars, and the massive increase of information flow from 5G networks. These events have led some experts to consider that we are now experiencing more supply chain disruption and innovation than we have experienced in the last 50 years.

While the deeper and more formal dive into supply chain management concepts was new for me, from early on, it was included in the "sciences of food fraud prevention."

The Challenge for Supply Chain Management

The disruptions are so extreme and so varied that it has become necessary to reset our expectations and the scope of our management systems.

Just as food safety is a specific area of science, supply chain management is a scholarly discipline. Supply chain management, which is focused on operations management, logistics, and distribution—or sourcing and procurement—is a common undergraduate business degree. Beyond master's degree programs, over 100 universities offer Ph.D. programs in supply chain management. A number of academic journals publish only on these topics. That said, a lack of awareness of the rigorous processes and procedures often characterizes this discipline. Supply chain management is often considered to be valuable only for manufacturing plant management, procurement, or transportation personnel. A vast and complex operations and communication network can be more efficiently engaged by a business' food safety business function.

To step back to the basics, supply chain management oversees the movement of everything from everywhere to everywhere else. At any time, anything can go wrong that will shut down an entire company. This the starting point—the challenge and everyday intensity of supply chain management.

Take a moment to consider some recent supply chain disruptions:

- The Suez Canal became blocked by a large vessel in 2021, causing a backlog of ships waiting to get through for a seemingly indeterminate amount of time (in total, it was 106 days)

- A Texas ice storm in February 2021 disrupted travel across the U.S. much longer than during a typical freeze/thaw cycle

- A computer chips shortage for vehicles has been seen since the start of COVID-19 supply chain disruptions

- COVID-19 is changing almost everything, from a massive shift in consumer shopping to an almost instant shift to curbside pickup and delivery, as well as radical shifts in the type of products that are in demand (think Peloton bikes and baking yeast)

- COVID-19 impacts the logistics and transportation networks from ports and facilities shutting down, as well as production and manufacturing stopping, then starting, and then stopping again

- Companies are having to quickly add supply and suppliers to keep running while balancing the risks of unknowns

- Companies are still having trouble keeping up with manufacturing, getting enough raw materials, and efficiently transporting their products to customers.

What has fundamentally changed is that our old way of responding is no longer possible. Basically, all the usual buffers were—or are still—gone, such as having safety stock, using backup suppliers, being able to expedite a few shipments to get caught up, being able to scale up from optimal utilization to maximum, or the option to increase lead times on deliveries. Think about these assumptions that are shattered:

- No automatic assurance of supply: In the past, if a product shortage arose, a company would usually just contact another supplier. Assurance of supply was available, even if it cost more to buy and transport the alternative product.

- No automatic alternate shipping routes: If a problem with one shipping route arose, other ways to get the product existed. If a port shutdown occurred, then the product could be moved through another port or more costly rail or truck transportation could be hired. At worst, if land and sea borders were blocked, air cargo transportation could be utilized. Once the COVID-19 pandemic hit, air cargo was booked solid and could not be obtained at any cost.

- No more "operating out of inventory": Everyone whittled down their inventory at the start of the pandemic. Everyone then tried to restock three months of safety stock instantly. The excess manufacturing capacity to ramp up did not exist. It became impossible for companies to operate solely on their own inventories, their suppliers' inventories, or to ask their customers to shorten their days-of-supply inventory.

- No more "just expediting shipments": This restraint has two challenges. The first challenge is never being able to catch up. It is impossible to get caught up when a company is two weeks behind, expediting orders, and only producing for the customer orders. The company will be stuck in paying or expedited shipping for everything. The second challenge is the transportation shortage, caused by a combination of unprecedented demand in the truck and rail industry and a commercial driver shortage.

- Consumer delivery has shifted from days to hours: It is amazing how frequently consumers order products online that are delivered later that day. Suppliers are placing more products closer to consumers to meet the increased competition in the marketplace. This also creates a massive spike in the amount of inventory that is held in the warehouses. These factors are fundamentally changing warehousing and logistics.

- No equilibrium, no patterns, no "normal": On top of these assumptions, the consumer demand, operations, and logistics have not been able to reach equilibrium. The supply and demand have continued to fluctuate, so the supply chain cannot catch up. Before the pandemic, disruptions and shutdowns due to a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) did not usually occur, but COVID-19 created that problem. Then the Ukraine–Russia conflict added another unprecedented supply chain disruption. All together, these many "events" and "effects" have led to a new and different type of inflation pressure. There is no equilibrium.

- The multiplication of all the assumptions: With some system equilibrium, the system could catch up even in the face of one of these factors. If one of these factors could be solved, then it would pressure the other factors.

The crux of the last year of supply chain management is that our problems have been initially shifted from "known knowns" (i.e., "simple" problems such as a delayed truck delivery) to "unknowables" (i.e., "chaotic," unforeseen problems such as at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine–Russia conflict). Over time, we might expect some consistency and shift to "unknown unknowns" (i.e., "complex" problems where we expect delays of some kind) or, with more information, a shift to "known unknowns" (i.e., "complicated" problems such as when we know suppliers may have trouble delivering on time, but we do not know what product). For further clarification, see the sidebar below.

Known Knowns? Unknown Unknowns?

Know Your Problem Type to Frame Your Response

If you do not understand the type of question you are answering, you may use the wrong tool. For example, detecting species swapping is very different than preventing country-of-origin labeling fraud. Known known? Known unknown? Unknown unknown? The classification makes a difference. So often, we—as humans, consumers, food scientists, criminal investigators, etc.—apply the same tool when responding to every problem.1

The "type of problem" classification system is helpful at the beginning of a food fraud investigation because it can provide the foundation for a more standardized response. When you realize the type of problem, then you can understand how the most efficient first step could be choosing an immediate cause-and-effect response (e.g., peanut allergen adulterant substance in cumin requires an immediate test for peanut allergen). In other cases, it may be best to start with a more complex active scenario development (e.g., trying to understand the evolving fraud opportunity seven days after Russia entered Ukraine).

Types of problems include:

- Simple (known known—e.g., water on the floor): For example, the risk of someone falling if there is water on the floor. These were the traditional supply chain management problems such as a supplier being unavailable or a truck getting delayed.

- Complicated (known unknowns—e.g., hurricane season): For example, the risk of supply chain disruptions from hurricanes over a year. It is known that hurricanes hit the U.S. Gulf Coast over a certain span of months, but precisely when they will arrive or their intensity are not known.

- Complex (unknown unknowns—e.g., most food fraud events): For example, most new food fraud events seem to fall into the complex/unknown unknowns category. (If the same type of food fraud keeps occurring, however, then the problem may become either a "simple" or "complicated" problem.)

- Chaotic (unknowables—e.g., Ukraine–Russia): The September 11 terrorist attack falls into this category, especially while that event was occurring. The Ukraine–Russia event probably falls into this category regarding food fraud and the food supply chain.1

Looking at these events from the last few years, what has become apparent is that the supply chain disruptions stemming from them are here to stay for a while. Also, there is a growing awareness that it is not wise to wait for things to "go back to normal," or to even try to predict the "new" normal.

The Foundation of Supply Chain Risk Management

We need a more methodical way to classify and understand to supply chain disruptions.

While supply chain management seems to be common sense, it is important to review the foundation and fundamentals before creating new methods or processes. Fortunately, the field of supply chain management has a long and rigorous body of work to draw upon. Specifically, the discipline focuses on supply chain risk, risk management, and classifying supply chain disruptions.

From the supply chain management literature come several important definitions:

- Supply chain risk: The likelihood and impact of unexpected macro- and/or micro-level events or conditions that adversely influence any part of a supply chain leading to operational, tactical, or strategic level failures or irregularities.2

- Supply chain disruption: Unplanned and unanticipated (event) that disrupts the normal flow of goods and materials within a supply chain.3

- Supply chain risk management (SCRM): The process of identifying, assessing, and mitigating the risks to the integrity, trustworthiness, and authenticity of products and services within the supply chain.4

- Supply chain disruptions: Unplanned and unanticipated events that disrupt the normal flow of goods and materials within a supply chain and, as a consequence, expose firms within the supply chain to operational and financial risks.5,6,7,8

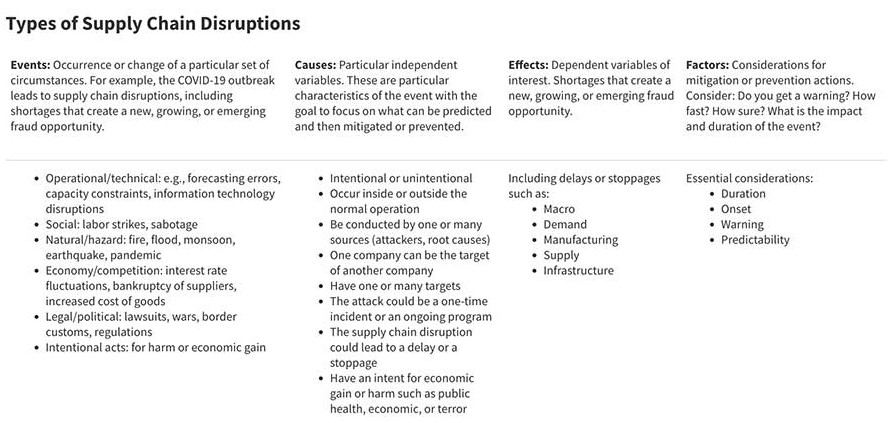

Supply chain disruptions may be viewed as events, risks, or vulnerabilities. The disruption can be classified by events, causes, effects, and underlying factors. The application of vulnerability is aligned with the food fraud prevention application.

This SCRM and supply chain disruption classification system is implemented in a formal and integrated plan that supports formal business activities such as advanced planning and scheduling (APS), sales and operations planning (S&OP), manufacturing scheduling, logistics scheduling, and into the corporate finance and accounting systems. The takeaway point for food safety management and food fraud prevention is that implemented systems already exist that can contribute to efficient control of risks and vulnerabilities.

The first step in addressing and preventing supply chain disruptions is understanding what kind of problem is being addressed. Not all supply chain disruptions are the same. When I started researching supply chain disruptions, I did not find a formal list or classification system. Also, pandemics were not a type of event. It was a challenge to figure out where a pandemic should be categorized. A pandemic is a root cause of other types of events. The "natural/hazard" category of a fire assumes a fire at your facility or a supplier's facility, not a forest fire in the region.

TABLE 1. Types of Supply Chain Disruptions

For food safety management and food fraud prevention, we now have a way to explain our problems in supply chain management terms. This supply chain disruption classification system helps define the full impact of the problem and the root causes. By using this classification, we can more efficiently utilize the supply chain risk management system.

Broader Scenario Planning

New, broader scenario planning is needed.

There is an efficiency in narrowing our focus to the most common and worst problems. We can refine our focus when we have stable problems and a lot of data. The current problem is that we are experiencing new problems, and we have very little, if any, useful historical data. Now what? What is normal? What is the "new" normal? How long will the new normal last?

Fortunately, we have a way to address this uncertainty. We have the perspective that food safety problems have evolved from "simple" or "complicated" to "complex" or "chaotic." When the future is uncertain, picking one way to respond might be simple, but it is more effective to utilize scenario planning.

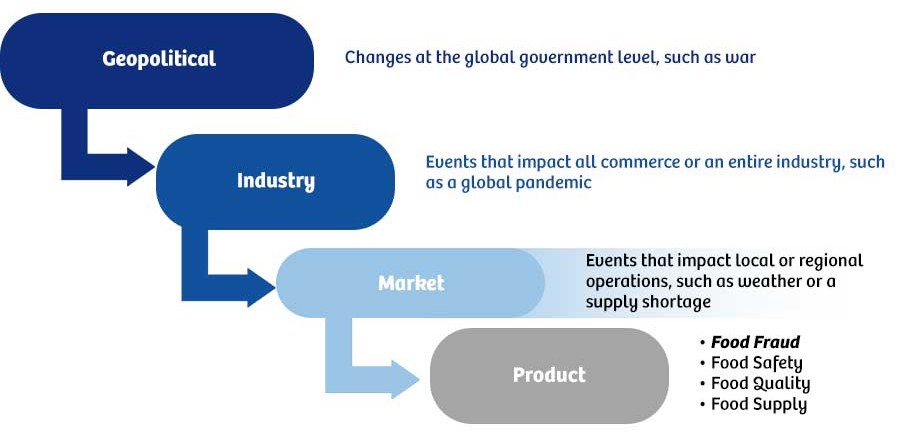

Scenario Planning

The supply chain disruption is total and completely uncertain, so the traditional resources and responses to food fraud prevention may be outdated. The entire landscape must be reviewed. Usually, we need to assess only simple scenarios such as how a shipment of product could impact our business (the result is a simple scenario and one action, so we do not even think about this as scenario planning). While a corporate strategy and board of directors-level risk committee would consider geopolitical scenarios, it has rarely been included at our front-line level. The result of scenario planning is to consider all the variables and then the full range of all possible future developments. Most probable scenarios will emerge. Also, based on the type of problem (simple, complicated, complex, or chaotic), a widening range of what could occur will be seen (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Hierarchy of Scenarios for Supply Chain Disruptions

Vulnerability Assessment Update

After identifying the scenarios that could occur—including the most probable and the range of higher potential—the vulnerability assessment can be updated. At this point, new incidents probably have not occurred and are not yet supply chain disruptions; however, some system weaknesses may exist that could cause them to appear. Also, there may be some pretty simple and low-cost countermeasures or control plans that can be put in place to reduce vulnerability.

Enterprise Risk Management Update

These scenarios and updated vulnerability assessment results should be fed into the Enterprise Risk Management (ERM/COSO) systems. This updated information will help inform the corporation of the shifting enterprise-wide risks. Also, this will calibrate which vulnerabilities have shifted above the risk tolerance.

Implement in a Real Management System

As defined by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and others, a formal management system is a set of policies and procedures that comprise the way in which an organization manages the interrelated parts of its business to achieve its objectives. For addressing food safety management, food fraud prevention, or supply chain disruptions, this is as simple as assigning team members, conducting regular meetings that are documented, conducting regular activities such as scenario development or updating vulnerability assessments, and then reporting the compliance progress to company management. More complex businesses operations may require more extensive documentation and controls to fulfill legal obligations and meet organizational objectives.

As an application, consider the Ukraine–Russia conflict. For example, Ukraine is a significant producer of sunflower seeds and oil. On the day that Russia entered Ukraine, the scenario planning would predict supply and demand problems for sunflower and related products, as it is known that stressed supply creates a food fraud vulnerability. The food fraud acts that occur during supply shortages are substitution, dilution, or short-weighting. Simple first steps could be to ensure that authenticity tests are being conducted, that the concentration is being monitored, and that the weights or volumes are being confirmed. Those steps probably reinforce existing work processes and would vastly reduce the food fraud vulnerability.

Takeaway Points

More rigorous work processes are also needed, so that we are not just chasing from one fire to the next.

New activities should be coordinated under a real management system. Often, the activities are a series of one-off, ad hoc responses to a problem or a project. If there were no real food fraud prevention management system in place, then there would have been no proactive review of the impact of the Ukraine–Russia conflict. It may have been surprising when sunflower product pricing spiked or when availability became constrained. It will definitely be surprising if the food fraud vulnerabilities become supply chain disruption events. If a real food fraud prevention management system had been in place, then these problems could have been prevented or at least mitigated.

Takeaway points include:

- Supply chain management concepts can be applied to food safety management

- Current food safety and food fraud risk assessment methods can be adapted to fit into supply chain management and corporate risk assessments

- For an efficient discussion of risks—specifically, a new risk explained in relation to all other enterprise-wide risks—the assessment should be calibrated with the overall, company-wide financial risks.

Action items include:

- Identify the team or accountable person (Is that you? Your supervisor?)

- Review your current documentation, methodologies, and procedures

- Review your audits and food safety management system (FSMS) standard to understand the scope and application of hazard identification

- Conduct a gap analysis of your food safety management and food fraud prevention to identify where early warning and proactive responses to disruptions could be improved

- Re-educate yourself and others before you start creating or implementing plans (see sidebar)

- And then, propose, get approval, and implement a management system.

Free Food Vulnerability Assessment Training Resources

To aid in re-educating yourself and others before you start creating or implementing plans, please take advantage of the free food vulnerability assessment training resources listed below:

- The Food Fraud Prevention Think Tank is offering a new, on-demand, Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) on Food Fraud Supply Chain Disruptions

- USDA Agricultural Marketing Service's Organic Integrity Learning Center offers online training that supports the professional development and continuing education of organic certifiers, inspectors, reviewers, and other professionals working to protect organic integrity

- Senior Stewards Acting for the Environment (SSAFE) seeks to unite the more than 4,000 residents at Kendal affiliates, residing in ten U.S. states, in addressing climate change at the global, national, and local levels to ensure a more sustainable planet

- The Food Authenticity Network (FAN) offers a variety of tools, publications, and training resources related to food fraud, food authenticity, and food safety

Together, these takeaway points and action items will help you and your organization create processes and procedures through a management system. The management system is a way to help organize your business to increase the efficiency of all activities, which starts with reducing disruptions. Food safety and food fraud are root causes of disruptions and so are key to your company-wide management system and supply chain management.

References

- Spink, John W. "Known Knowns? Unknown Unknowns? Know Your Problem Type to Frame Your Response." July 19, 2022. https://blog.foodfraudpreventionthinktank.com/known-knowns-unknown-unknowns-know-your-problem-type-to-frame-your-response/.

- Spink, John W. Supply Chain Management Introduction: Sourcing, Operations and Logistics. Jacksonville, Florida: York Partners LLC. To Be Published (2022). www.scmintro.com.

- Spink, John W. "Food Safety as a Supply Chain Management Problem." Presented at Food Safety Summit, Rosemont, Illinois. May 12, 2022.

- Craighead, Christopher W., Jennifer Blackhurst, M. Johnny Rungtusanatham, and Robert B. Handfield. "The Severity of Supply Chain Disruptions: Design Characteristics and Mitigation Capabilities." Decision Sciences 38, 1 (2007): https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2007.00151.x.

- Svensson, Göran. "A conceptual framework for the analysis of vulnerability in supply chains." International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 30, 9 (2000): https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/09600030010351444/full/html.

- Hendricks, Kevin B. and Vinod R. Singhal. "The effect of supply chain glitches on shareholder wealth." Journal of Operations Management 21, 5 (2003): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2003.02.003.

- Kleindorfer, Paul R. and Germaine H. Saad. "Managing Disruption Risks in Supply Chains." Production and Operations Management 14, 1 (2005): https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2005.tb00009.x.

- Stauffer, David. "Supply Chain Risk: Deal With It." Working Knowledge. April 28, 2003. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/supply-chain-risk-deal-with-it.

John W. Spink, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Supply Chain Management in the Eli Broad College of Business at Michigan State University. He is also the Director of the Food Fraud Prevention Think Tank.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!