A Closer Look at Environmental Monitoring in the Processing Plant

Strategic Consulting Inc. and Food Safety Magazine surveyed more than 100 food processors throughout the United States on their preparations for compliance with the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and how elements of their food safety programs may be changing as a result. In this article, we’ll present our findings on the changes reported in environmental monitoring and sanitation programs and how the analytical testing procedures that processors use may be changing.

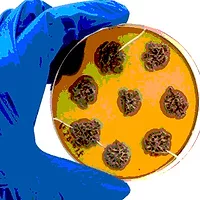

We asked processors about any changes they had made to their environmental monitoring (EM) programs in response to FSMA (Figure 1), in terms of both the numbers and types of samples they would be collecting and the sample analysis used on them. Processors were split in their responses, with the number of respondents saying they would be collecting more samples roughly equal to the number who said their sample volumes would remain mostly unchanged. This answer varied only somewhat by type of processor, with approximately 40 percent of fruit and vegetable processors, 45 percent of processed foods processors and 50 percent of dairy processors saying they would be taking additional samples, with the major exception being the protein sector, where all processors indicated that they would neither be making changes to their EM programs nor collecting additional samples.

Enter the FDA and Its Methodology

Knowing that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has indicated its intent to more frequently collect swab samples during inspections, we also asked processors whether they plan to specifically increase the number of EM swab samples they collect or sample more locations prior to FDA inspections. Seventy percent of respondents indicated that they have not changed their programs in response to any FDA programs. Of the 30 percent of companies that indicated that they have made changes, they reported that they will be taking more samples and in more locations, and using the samples to test for more pathogens than they had been looking for previously, with Listeria most often mentioned. Outside of surface swabs, other EM program changes reported included adding sampling and analysis for specific media, with additional sampling of process and wash water most frequently mentioned, and more staff EM training. These companies also said that they will be increasing their testing of incoming raw materials and final product as well.

Understanding that when FDA collects additional swab samples that these may be analyzed using whole-genome sequencing (WGS), we asked whether companies would also be submitting their own samples for WGS. Ninety-three percent said they would not be using WGS and that they had made no changes to the analyses they use for samples. Of the seven percent that indicated they would be using WGS, none said that their decision was specifically in response to FDA, but they indicated that WGS “is good data to have.”

“Whole-genome sequencing is a powerful tool,” said David Acheson, former FDA associate commissioner for food and current CEO of The Acheson Group, “but we understand the reluctance of some processors to develop data that can be discoverable. But it is clear that processors need to find (and the FDA is encouraging them to find) any resident strains that may be in their plant. Other diagnostics like PFGE [pulsed-field gel electrophoresis] can work, but WGS does work and it is the way the regulatory agencies are moving. But if you are repeatedly seeing the same pathogen in your plant that may be resident, and a food safety incident results, any lack of action on your part to identify and correct a resident strain due to a reluctance to use WGS will be no excuse.”

For an illustration of how this use of WGS will enhance traceability, particularly of resident strains, consider the following example offered at the Food Safety Summit in May from Dr. Robert Tauxe, director, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne and Environmental Diseases for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tauxe cited French regulators who were working on a recurring Listeria cluster in a hospital where there were repeated outbreaks of small numbers of people getting sick. The French officials, using WGS on cultures recovered from ill patients during one of these outbreaks, were able to genotype the organism and match the source to resident organisms found in samples from a specific piece of equipment in the hospital. Once that equipment was cleaned and the source removed, they saw no more incidents.

This is a clear lesson for food processors and a model of investigations they can expect to see more often, where WGS will be used to pinpoint the exact source of contamination responsible for a food safety incident.

“The FDA is a strong believer in whole-genome sequencing as a method to identify resident organisms,” said Jenny Scott, senior adviser, FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Food Safety. “It is not the only way, but we encourage facilities to use one of the analytical techniques available to identify resident strains. We will be asking our inspectors to pay attention to the environmental monitoring data at a facility but [pay] particular attention to the corrective actions taken, and in those facilities where they have an ongoing program and they are sharing the results, the results look good, they are sampling in the right areas, the facility has good CGMPs [Current Good Manufacturing Practices] in place, there may be no point for us to take any samples in a facility. Any positive findings can be mitigated by the right corrective actions. We don’t expect facilities to never find a positive—we hope they will occasionally find positives—but the focus will be on the corrective actions taken and making sure there is ultimately no problem with their product.”

Legal Considerations

Understanding that companies may be wary of developing data that may be discoverable or will have to be produced during an FDA inspection, we also asked companies whether they were considering working with an attorney in the management of their sanitation program. Ninety-one percent of the respondents replied that they have not been working with an attorney and they have no plans to change. Of the remaining nine percent who indicated that they are or do plan on working with an attorney, about half reported that they have an attorney to review their data regularly, and the other half said they will call in their attorney in case of an incident.

We talked with Shawn Stevens, a food industry lawyer from Food Industry Counsel LLC, about developing data using WGS and working with an attorney as a regular part of a sanitation program.

“Food processors need to be careful not to try to use routine solutions that worked in the past to solve these new and unique problems,” said Stevens. “The situation we are in is clearly different [from] what it has been in the past, particularly the approach of the FDA and the prospect of ‘swab-a-thons’ and the increased risk of criminal exposure. Companies need to use new, ‘nonroutine’ methods, both analytical and legal, to navigate through what has become an unmarked minefield.

“Using WGS is not absolutely necessary, but finding and eliminating niche organisms is. To the extent that genetic typing is needed in that effort, it should be used. We generally recommend a three-stage process, which consists of first finding out if you have a problem and if niche-harborage organisms are present. To do this, a company must swab and test their facility through an ‘aggressive hunt.’ Second, once and if organisms are identified, eliminate the problem through decontamination processes. Third, if the first two steps are not effective because of the likelihood that multiple genotypes are present and you need higher resolution in your analytical method to better identify and characterize the problem, then employ WGS to get that data you need, get the right characterization and identification and clean again.

“As for doing this with or without the help of an attorney, there is an argument that this work is not part of your written FSMA plan and is therefore outside the purview of the FDA. This may turn out to be the case, but this is by no means certain, and having an additional layer of protection and additional guidance in the process to avoid the errors that can increase exposure in this uncertain risk environment will help manage the risk. It may even help convince senior management to take these necessary steps, knowing the risk is better managed.”

A Look at Sanitation

We also asked processors about changes to their sanitation programs (Figure 2). Forty-one percent of the respondents said they have made changes to their sanitation programs, with roughly one-third saying the changes were “significant.” Of the remaining 59 percent who said they have not made changes, two-thirds of these respondents indicated that they believe their program is effective and does not require change. We also asked about the impact on their sanitation programs from employee turnover, the impact of retention-incentive programs and their attitudes toward outsourcing their sanitation programs; we received more details and data than we have room for in this column. Look for more details of these results of our survey in a future Food Safety Insights column.

Bob Ferguson is the managing director of Strategic Consulting Inc. and can be reached at foodsafetyinsights@gmail.com or on Twitter at @SCI_Ferguson.

Looking for quick answers on food safety topics?

Try Ask FSM, our new smart AI search tool.

Ask FSM →